As we can read in Apache commons Chain a Context represents the state of an application and can be considered an envelope containing the attributes needed to complete a transaction.

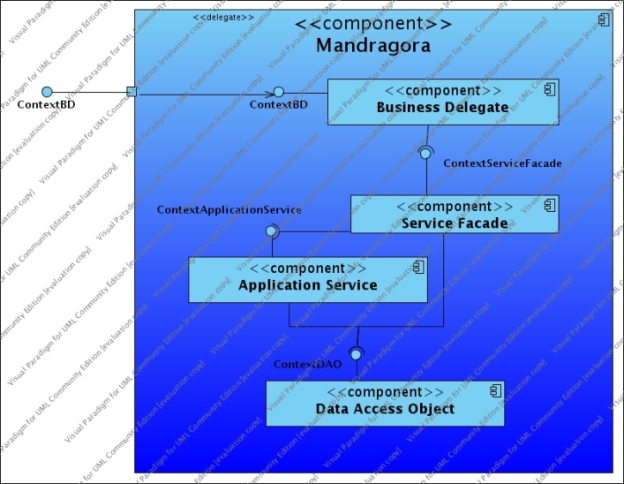

Mandragora could be seen from a front controller point of view, as a set of operations, or services provided by the BD (Business Delegate) interface, which we have to supply to some input parameters to have the job done and have eventually some object returned.

The controller doesn't know how the job is done, but the architecture designer knows that the parameters provided by the input are pushed down trough many tiers, and each tier can be considered to do a unit of job, using the initial input parameters, and eventually producing new ones to push down in the next tiers to complete the job. Such tiers, on the back of the business delegate, are the Service Facade, Session Facade, Application Service, and DAO.

This approach has the limit to tied different tiers trough the parameter, so if we refactor some method so that it needs different parameters, we have to refactor its callers as well, so refactor along all the chain could be needed.

To avoid this we can use the Context, that is a kind of Map, that holds all the parameters needed.

So moreover than the BD interface methods, mandragora provides an other set of methods, specified by the interface ContextBD. This interface holds the methods with the same names as the methods of BD, and have one only input parameter that is a org.apache.commons.chain.Context instance.

Note that in the BD interface we can have many methods with the same name and many signatures, such methods are collapsed in just one in the ContextBD, and its behavior depends on the values that can be found in the Context.

For example, about the method findByPrimaryKey, we have in the BD interface:

while in the ContextBD interface we have just

In the same way that BD uses ServiceFacade to do its job, that in turn uses ApplicationService and DAO, the same relationship exists between ContextBD, ContextServiceFacade, ContextApplicationService, and ContextDAO,

Mandragora comes with some ContextBD, ContextServiceFacade, ContextApplicationService, and ContextDAO implementations, that can be extended, or new ones of such implementations can be written by the user.

We have to consider two kinds of parameters: logic parameters, and context parameters.

We call logic parameters the ones that are needed to perform the real job of the method, for example sum(int a, int b) a and b are logic parameters.

We call context parameters the ones needed to set or configure the context, or environment in which the job has to be done. For example they could hold information about transactions, about the real implementations of the interfaces and so on.

About the logic parameters we have to say that as the name of a method have to suggest something about its meaning, in the same way, the name and type of its parameters, should help understanding its behavior, having to be considered part of its formal definition. If we use a Context instance as unique formal parameter, the name, number and type of logic parameters are fully hidden, leading to a loss of readability.

A second drawback is that if we put all parameters in the Context, in the body of the method we have to check if they really are in the Context instance and if they have the proper type, forcing us to do an extra effort in writing validating code, and above all, errors will be detected at run time in place of compile time.

A third drawback is that the implementation of the method is tied to name of the parameters in the Context, as the code implementing the method has to look in the Context for a value mapped to a key that has to be the same used by the caller to put the parameter in the Context instance. So the method caller and the receiver must share a knowledge.

Anyway the org.apache.commons.chain.impl.ContextBase helps a lot to reduce the impact of this drawback.

About context parameters, in place of being provided as formal parameters, they are often provided statically with external configuration files, (xml or properties) that we can consider giving default values. But if we want to change them dynamically at run time, as the typical case of dealing with two databases and wanting to decide at run time which one has to be used, they have to be provided as formal parameters.

If we consider a generic method, that have to do an abstract job, as a functional unit (or unit of function or unit of service) we want to concentrate on its abstract and functional meaning, and not on the environment or context in which it will be executed; so we don't want to tied context parameters to the definition of the function, that is, we don't want to see them (explicitly) between its formal parameters.

So to put context parameters in the Context instance is a good idea.

What could be the solution? Well the first thing that can come in mind is use formal parameters for logic parameters, more an other formal parameter that be an instance of Context where to put context parameters. A method with a signature like this

| method(String par1, Integer par2, ... , Object parN, Context context) |

But as we are using a context, we want to leave an open door to the implementation of command and chain of responsibilities patterns. So, for the moment, we discard such idea (even if not completely as in some extension it could be useful).

Our solution will involve the use of proxy classes, that hold an instance of Context to push down the architecture the context parameters, without altering the traditional call of a method, passing to it just the logic parameters.

The idea of injecting context parameters without putting them between the formal parameters is quite easy. The class holding the method to be executed must hold as property, with its setter and getter, an instance of Context; concretely we will use MandragoraContext, that is an extension of org.apache.commons.chain.impl.ContextBase. Before to call the method, the caller should get the context instance (with the getter) and should put inside it the context parameters; then it has just to call the methods passing its formal parameters.

So by the caller client point of view, it should lookup some implementation that have a MandragoraContext property, push inside it its context parameters, and do its calls. This is what should be seen by the client that use the service. Let's see now more in details which features have such implementations in Mandragora.

The ContextHandler is a Mandragora class of the package 'it.aco.mandragora.context' to handle and manage Context instances (concretely MandragoraContext instances).

It holds a property named localSession, with its setter and getter, that is of the class MandragoraContext. The implementations we are talking about extend ContextHandler, so that we can get the localSession and put inside it the context parameters.

For example:

| BD bd = ServiceLocator.getInstance().getManagerBD("someBDFactoryClass","someBDClass"); MandragoraContext localSession = (MandragoraContext)((ContextHandler)bd).getLocalSession(); localSession.put("jcdAlias","testdb2"); bd.insert(petVO); |

The insert method will act on the testdb2 database.

The ContextHandler has the method

that create and returns a new instance of MandragoraContext that has been filled with all the parameters of the ApplicationContext, of the localSession, and of the input parameter request.

This could be enough to know by the user, but it should be useful have a look at its implementation to see how the ContextBD, ContextServiceFacade, ContextApplicationService, and the ContextDAO are involved, to understand how to use them deeply extending them, and how this piece of architecture leave an open door to the command and chain of responsibilities patterns. To do that have a look at the following Proxy Handler section.

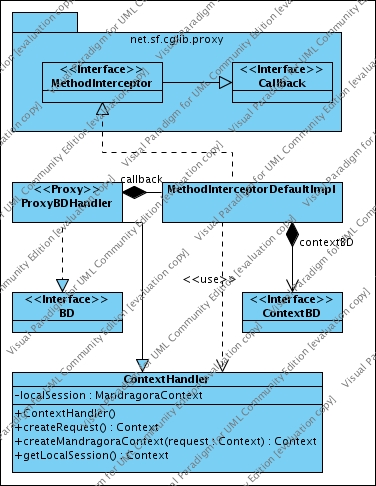

A dynamic proxy class is a class that implements a list of interfaces specified at runtime when the class is created.

We use Cglib to create dynamically an implementation of the interfaces of the J2ee patterns (BD, ServiceFacade, ApplicationService, DAO), that extend ContextHandler.

We define Context Pattern interface one of the interfaces ContextBD, ContextServiceFacade, ContextApplicationService,and the ContextDAO.

We define Pattern interface one of the interfaces BD, ServiceFacade, ApplicationService, and the DAO.

We define Proxy Handler a proxy class that implements a pattern interface, extends ContextHandler, and calls back a MethodInterceptor that holds the correspondent context pattern interface.

For example for the BD interface we have:

When a method of a proxy BD is called, what goes on is the following:

One of the benefits of introducing the concept of the Context in Mandragora is to bring the Mandragora Multi-tiers (or N-tiers) architecture closer to the chain of responsibility pattern. The main difference between them is that chain of responsibility pattern tries to abstract a sequence of command, while an N-tiers architecture tries to abstract a service. In the multi-tiers architecture each tier provides services to its closest higher tier, and to implement them uses the services provided by its closest lower tier. The top tier provides services to the client that is using the architecture.

Anyway we can consider both of them to provide a service to the client, as in both cases the client wants some operation to be performed without having idea about how.\

There is a difference between the commands of a chain of responsibility and ones of ContextXX interface, and is about the way they return the result, that is explicitly on the ContextXX and trough the Context instance in the case of the commands. But this could be changed in the future, and nothing forbid to use both approaches, putting the result in the context, and at the same time return it explicitly.

Anyway we can't consider the chain of tiers (BD, Facade, ApplicationService and DAO) a chain of responsibility, because the different tiers are not a sequence of commands as if they were like the following:

1 execute BD

2 execute ServiceFacade

3 execute ApplicationService

4 execute DAO

But if we look layer by layer, we could find the following:

A BD method performs some lookup operation and then executes a facade method. It could be that we could consider it as a sequence of command.

A Facade method can be viewed as a sequence of commands.

To see an Application Method as a sequence of command is very hard, because if it was, it could be considered a facade method, and should be at facade level.

So we can conclude that our architecture could be seen by the client as a catalog of commands, and as well, the BD layer could see the services provided by the facade as a catalog of commands, and ServiceFacade could see the services provided by ApplicationService and DAO as two catalogs of commands. Each one of such command is a chain of commands each one of which in turn can be a chain of command of the closest lower level: (BD: the chain look-up , servicefacace execution; servicefacade is the chain of DAO and ApplicationService commands).

In this way we could think that Mandragora could provides in a future a catalogs of commands, following the command pattern, described in xml file using the apache commons chain framework, and if we would to add some command, we had just to update the xml catalog.

Imagine you need a new BD command, that need a need a new ServiceFacade command, that could be expressed in terms of a chain of existing DAO and ApplicationService command. Just working on the xml file, we could have available the new command at the BD level.

So one benefits of the context is to leave an open door to the catalog of commands.